True

Ding. Floor 1.

I lay my body on the side of the elevator walls. My bookbag slides further and further down my small arms.

Ding. Floor 2

My brother and his girlfriend (whose name I can’t remember) hold hands behind me. They haven’t let go since picking me up from school and somewhere along the way I had tuned them out.

“Katelyn, you looked Indian when I first met you,” she said.

Suddenly I’m pulled out of my thoughts at the sound of my name. I turn to look at her for the first time today, bewilderment in my eyes. She senses the confusion and continues to try to get me to understand.

“You don’t look Dominican like the rest of your family, like your brother.”

She points at him and my eyes follow.

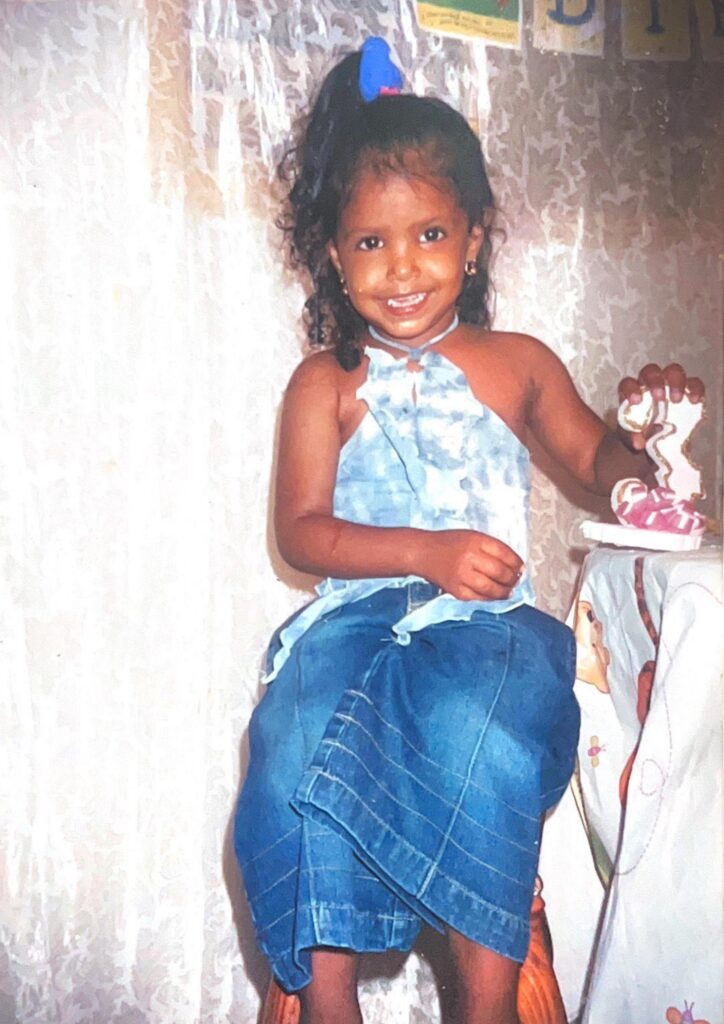

Now I won’t pretend to have never noticed that I’m brown and my brother is not. I was 8, not ignorant. But before this moment I didn’t spend much time thinking about what I looked like let alone what I didn’t look like to others.

Ding Floor 3.

Both of my parents settled in Washington Heights when they left their home country. It’s not surprising that although they came at separate times in their lives for different reasons, they still ended up in the same place. Most of the people who live in the Heights manage to retain their same voice, language, and appearance as if they were still on the island. That’s why it’s called little Dominican Republic.

And my parents are as Dominican as it gets. It doesn’t just run through their blood, but their lungs wouldn’t function properly without their culture. Their loud voices that were heard before they entered a room, commanding the space. They’d tell everyone they encountered about their slice of the island, describing it like a dream space that will never be forgotten. Even as the years go by and they become accustomed to life in America. Reborn New Yorkers, with their hearts left behind in the caribbean.

But unfortunately for them, it seems like they were given the wrong baby at the hospital.

I was shy, soft-spoken, and never wanted to take up too much space. I didn’t dance bachata at the family parties. I didn’t eat the enormous bowl of sancocho served for dinner. I didn’t speak Spanish most of the time despite it being my first language . I wanted nothing to do with any of it. I was an imposter living around people who weren’t afraid to be loud and boisterous. They all knew exactly who they were their entire lives and I didn’t just envy them for it— I hated them for being a representation of all the ways I wasn’t working properly. And to add to that chemical imbalance, I didn’t even look the part.

_ _ _ “Diaz!”

“Here.”

“Diaz?”

“Here!” I raise my hand higher.

“Oh, you don’t look — where’d you get that last name from?”

“Uh …”

My hands started fidgeting, my body was getting concerningly hot. All the eyes in the classroom were on me. I must have done something terrible in a past life to be living this nightmare. This wasn’t how I had planned it in my head; she was supposed to stick to the script. I looked down and then up, stuttering my words as I tried to answer. The simple, obvious answer was my dad.

Most people in this room, including my Spanish teacher, Miss Rosario, were given their father’s last name. I knew that’s not what she was looking for. She was hoping I’d say something that miraculously explained how someone who looked like me could get a Spanish last name like Diaz.

This was the first day of high school and she continued to ask that question a handful more times throughout the school year. I told her on that same first day that I was Dominican as I nodded at the large Dominican flag she had displayed in her classroom, in hopes of solidarity. But every time she asked, every time she questioned, I felt further and further away from her and myself.

Closer to the end of the school year, Miss Rosario asked everyone to bring in food so we could have a party in the classroom. I brought in what I thought would prove who I was and where I was from.

Pastelitos.

A savory pastry with a warm filling with endless possibilities. It was the hit of the party with only flakes from the crust left in the tin trays. Miss Rosario raved about them, telling me she was so glad I knew the right place to get them from.“Not everyone makes them correctly,” she kept repeating. We were finally bonding but whatever I was chasing — whether that was approval or tolerance — it wasn’t relieving. I couldn’t just wrap my identity in a bow and make it pretty.

My mother spent $40 on those pastelitos for my class that day and suddenly my identity had a price tag.

Now as I look back to those moments, I realize the hate I was carrying.

Hate for the color of my skin.

Hate for the shape of my body.

Hate for my quiet nature.

I hated that all those innate, intrinsic qualities of mine were considered “not Dominican.” My brother’s middle school girlfriend was the first person to ever point out the difference in me and she wasn’t the last. After that moment everywhere I went with my light-skinned, sociable, fitted Yankee cap-wearing father, people would place bets that I wasn’t his. Some would even bless him for adopting a little Indian girl. He’d then tell me I had to spend less time in the sun.

And I did.

I still cringe every time someone asks the dreaded question, ‘Where are you from?’ I watch them analyze my face trying to make sense of it and I watch the skepticism in their gaze when I answer. I’ve stumped them. It doesn’t upset me anymore. The displacement is unexpectedly comforting. Knowing it makes it harder for them to put me in one box.