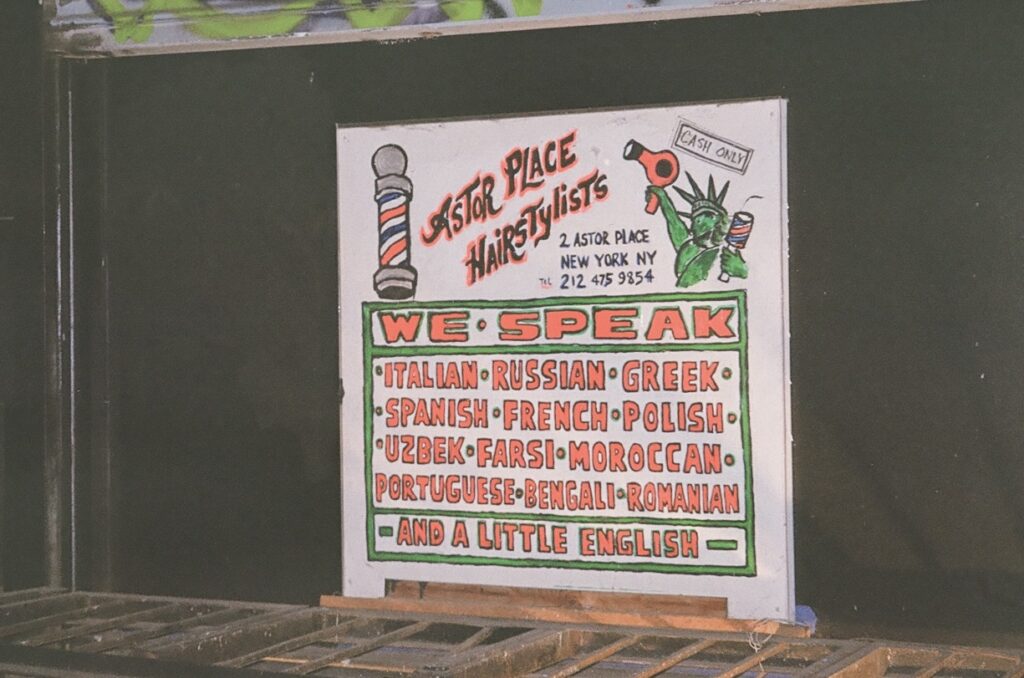

New York is the most linguistically diverse city in the history of the world. In no other time and place have humans spoken as many different languages as New Yorkers do now. The most common tongues belong to hundreds of thousands or even millions, entire cities worth of people speaking Spanish, Chinese, Russian, and Bengali.

As Ross Perlin writes in his new book, Language City: The Fight to Preserve Endangered Mother Tongues in New York — published in February by Grove Atlantic — these most common languages account for only a fraction of those spoken in the city. Over 700 documented languages are spoken in New York, and around half of all New Yorkers speak something other than English at home. Throughout the city, and most frequently in the outer boroughs, entire neighborhoods have blossomed around immigrant subgroups who’ve brought not only their people, their religions, their customs, their food — but the very words that make up the fabric of their lives. They range from Punjabi-speaking Sikhs in Ozone Park, Queens, to Arabic-speaking Palestinians and Yemenis in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, and everything in between.

Packed into every corner of the city are people who speak languages most have never heard of — some with only a minuscule number of speakers left. These exceptional cases are the focus of Perlin’s book and much of his career. A linguist and professor at Columbia, Perlin co-founded the nonprofit Endangered Language Alliance, where for years, he and others have worked to catalog and safeguard these rare languages.

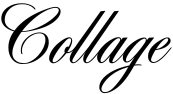

The book is impressive in scope, covering the history of the city’s evolving linguistic landscape from pre-colonization Lenape, through Dutch and English settlement, and onto our current era of global migration that has made New York a stitched-together patchwork of languages and a microcosm of the world itself. It uncovers the power that linguistic diversity brings to cities, pushing so many different people so close together. It also explains why languages die and what can be done about it. But all of this is the preamble to the heart of the book: the stories of six present-day New Yorkers, all speakers of endangered languages.

They include Husniya, a speaker of nine languages hailing from a mountainous region of Tajikistan. In her native Wakhi, spoken by only 40,000 people worldwide, she recounts magnificent fairy tales carried down through generations. Now living in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn, Husniya sees fellow Wakhi speakers, by necessity and convenience, living more of their lives in English. She hopes that by writing storybooks for children in Wakhi, she will help keep the language alive for the next generation.

If 40,000 speakers constitute an endangered language, the 700 remaining speakers of Seke, hailing from just five villages in Nepal, are holding their language back from the precipice of extinction. Remarkably, over 100 of them have moved to a single six-story brick building in Flatbush, Brooklyn — making this “vertical village” the sixth Seke home. Rasmina, in her early twenties, is our guide to this incredible scene as one of the youngest remaining speakers. Her younger cousin, who came to New York at age three, only understands Seke depending on the context. His Spanish, from five years of lessons in New York City public schools, is better than his mother tongue.

As Perlin makes clear, the phenomenon of endangered languages in this city is a more expansive and complicated one than these examples of recent immigrants from rural corners of the globe may suggest. In Boris, we meet the former editor of a Yiddish newspaper who is contemplating the evolution of his language. Hasidic Yiddish has boomed in New York; half of its speakers here are under 18. But this form of Yiddish is heavily tied to religious institutions Boris does not belong to, and differs substantially from what he grew up speaking in present-day Moldova. Now, Boris is one of the few remaining writers of secular Yiddish literature. Karen, meanwhile, seeks to bring the indigenous Lenape language back to New York, where it has survived only in place names twisted from the original — Gowanus, Canarsie, Manhattan. Karen’s efforts to teach Lenape draw numerous interested students, many of whom have Native heritage. Their own ancestral languages are, in many cases, extinct or impossible to reconstruct, but Lenape remains the closest living cousin.

Perlin deftly weaves in his perspective as a linguist and activist without overshadowing the incredible stories of his subjects. His own family shows how centuries of linguistic history can unwind in mere decades. All eight of his great-grandparents were multilingual Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe who arrived in New York around the beginning of the 20th century, speaking combinations of Yiddish, Polish, Russian, and German. Their children’s English was the accented strain dominant in Jewish neighborhoods in Brooklyn and the Bronx. In the age of mass media, Perlin inherited from his parents the type of “accent from nowhere” that one hears all over the United States.

Language City is an enthralling read for curious New Yorkers who wish to dive deep into one aspect of their endless city. But readers everywhere can appreciate how salient Perlin’s focus is in an era of persistent nativism and xenophobia. He spends most of Language City in the past and present, but questions of the future course throughout the entire book. Perlin stands against the anti-immigration sentiments that right-wing politicians and activists have spent so much energy inflaming in recent years. He decries the city’s rapidly growing cost of living and ponders what it might mean for speakers of endangered languages. Above all, he calls for a citywide effort to reorient our thinking beyond a simple celebration of diversity as an amenity: “It has to be less about restaurants and ‘glocal’ tourism,” he writes, “and more about the day-to-day needs and desires of neighbors who speak hundreds of languages.” That means more multilingual education, more information available in more languages, and more spaces where endangered languages can survive, and even thrive. Otherwise, we risk losing more than the words people speak — we might lose the stories, memories, and cultures that have made this city truly global.