At first glance, the residential buildings on 4th Street between Cooper Square and Lafayette Street look quite similar. Yet hidden amongst them, dressed in warm-toned late-federal bricks, is a four-story house with steep marble steps and forest green wrought iron railings.

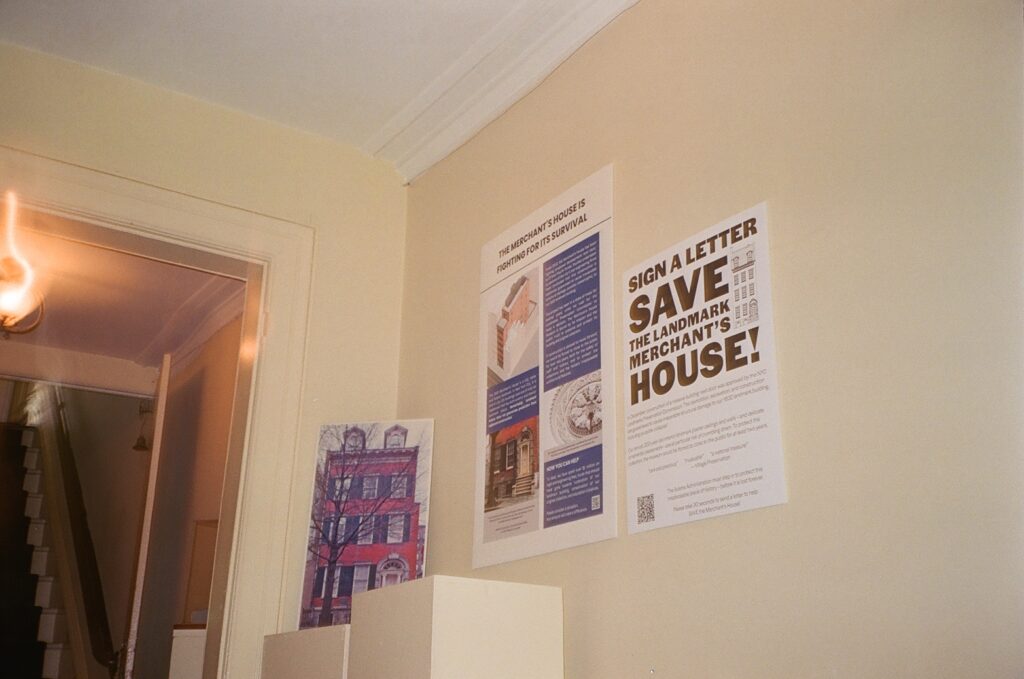

A big sign sitting outside the house, confronting passersby, reads “SIGN A LETTER SAVE THE LANDMARK MERCHANT’S HOUSE!” Perpendicular to it hangs another sign, in red, facing onlookers walking up from Lafayette Street that reads “OPEN.”

The Merchant’s House Museum is an exactly two minute long walk from 20 Cooper Sq., perhaps three minutes if you drag your feet to class. As a student at New York University’s Arthur L. Carter Institute, I had walked past the House numerous times — at least three times a week for class— and never quite noticed it.

And that has always been the modus operandi of the House. No big flashy signs. Those who know, know and those who know, visit. But lately the House has been practically begging for attention so I took the bait. One day in early April I paid it a visit.

Atop the seven rather steep steps that lead to the front door, patrons speak into the speaker to be buzzed in (the most modern addition to the House, in my opinion). The minute you step inside, you are transported back to 1832 when the House was built.

The ceilings are adorned with delicate plaster moldings. Chandeliers hang down like earrings, and blood red curtains decorate certain windows. Everything is intact, including furniture, antiques (now more so), clothes and the everyday items that belonged to the Tredwell family, who lived in the House for almost a hundred years.

The intricate details that make the House special – such as the delicate decorative plastering work on the ceiling – run the risk of being ruined should the vibrations, from the construction next door, cause them to chip off or break.

The House was the first building in Manhattan to be designated landmark status in 1965, putting it under the protection of the Landmark Preservation Commission. However, for the last 12 years, the House has been fighting against looming construction plans next door — 27 E 4th street.

The Landmark Preservation Commission, “is responsible for protecting New York City’s architecturally, historically, and culturally significant buildings and sites by granting them landmark or historic district status, and regulating them after designation,” according to its website.

In the last three years, the LPC which sees itself as the “largest municipal preservation agency in the nation,” has approved the demolition of ten buildings under its protection and allowed damage to six others. It is no wonder that the volunteers, who largely run the House that exemplifies well-preserved architecture from the 19th century, are worried about the House’s fate.

“They should be called the LDC: Landmark Demolition Commission,” said Rita Davis, an outraged volunteer at the museum and New York native. Davis also expressed her bafflement with the ironic role of the Commission in the state of things.

Some preservation architects and engineers employed by the House have analyzed the proposed plans and determined that construction in the adjacent plot would cause guaranteed irreversible damage. The intricate details that make the House special — such as the delicate decorative plastering work on the ceiling — run the risk of being ruined should the vibrations cause them to chip off or break.

Although the developer’s engineers maintain that the construction will not cause harm,

“You’re going to build a 7-9-8 story thing, that is going to go back 100 feet, and you’re telling me that that weight is not going to cause an issue for the Merchants House?” said Pi Gardiner who has been the Executive Director of the Merchant’s House Museum for over 30 years.

The developers, Kalodop II Park Corporation, and the Merchant’s House Museum got off on the wrong foot and have remained at odds through the last twelve years.

It all started at a Community Board meeting in May 2012, a meeting where developers presented their plans for the plot next door — a parking garage — that, Gardiner alleges, the MHM did not know was happening. On request, the meeting was repeated for MHM.

When plans by the developer were first being proposed, they were for an 8-story hotel. Due to zoning issues this was changed to be a 7-story office building instead. During the considerable back and forth that ensued between the MHM, the LPC, and Kalodop, the House had collected damning engineer reports and plaster studies that supported what they were worried about. The House just wouldn’t be able to take it.

In February 2021, the LPC decided that the best way to tackle the issue would be to have the two camps, MHM and Kalodop, join forces. The LPC instructed them to combine engineers and architects to collaborate and come up with a feasible protection plan.

And so for about 2 years, the two teams worked together. Everything seemed copacetic.

But then, in what Gardiner described as an “out of blue” turn of events, the LPC issued the House with a five-day notice to appear before the commissioner for a meeting in December 2023. Since the developers called the meeting to present plans before the LPC, the House would not be allowed to speak at the meeting. They were only allowed to consult with their engineers during the five days they were allotted and sent in written testimony.

The museum’s team and lawyers felt blindsided by what had happened. They watched helplessly as the developers made their case.

Harry Kendall, partner at architecture firm BKSK, said that since their last presentation in 2021, they had been “challenged” to check soil conditions and dig an additional test pit.

“We are bending over backwards to protect the neighbor,” Kendall, who was the first to present at the meeting, said.

“We believe a more intact urban fabric will benefit the block in general and we can provide a healthy context for the Merchant’s House Museum going forward,” he added before handing over the presentation to fellow partner at BKSK, George Schieferdecker.

Towards the end of his presentation, Schieferdecker said that “the Merchant’s House [is] an important landmark that we care about and it’s very important that our building stay clear of it.” He assured the meeting attendees that the new building would distance itself from the parting wall that lies between the House and garage currently.

In his presentation, Karl Rubenacker, a construction engineer at Gilsanz Murray Steficek, LLP. (GMS) revealed that the test pits made in 2012 showed that the existing foundation of the Merchant’s House appeared to be sitting on undisturbed granulated soil that goes up to eight feet down.

The geotechnical investigation had two borings, which revealed that the bedrock is about fifty feet down, the water table is about forty feet down and then there is forty feet of “nice sandy soil” up until the bottom of the excavation when they built the original buildings.

What all this means, according to Rubenacker who clarified he is not a geotech, is that the foundation “of the merchants house” rests on “nice stuff.”

In terms of the structure of the building itself, the engineer implored that they have made the building “as light” as they “practically can,” using a steel frame in addition to making it shorter than initially proposed by one floor. “It’s not just about the design of the building, it’s about how it is implemented,” he said, explaining that the project next door to the House would be initiated in sections.

At the end, the LPC approved construction for 27 E 4th St.

“The LPC’s decision is hugely disappointing,” said Neil Polich, the Museum administrator. “They signed off knowing the Merchant’s House likely would not survive the development.”

The timing of LPC’s approval also seems confusing because the city of New York, through the parks department, has recently announced that it plans on starting a $3.2 million restoration on the House later in the year. So the question is why not stop the construction next door preemptively, as a precaution, rather than do damage control after the fact?

Should the construction next door proceed, the museum will be forced to temporarily close its doors to the public for about two years, according to Gardiner. It will also have to hollow out the house and transport treasured artifacts and furniture to a storage unit. Other precautionary steps, with no guarantees, will have to be taken to try and protect the plaster.

The legal procedures along with all the research the MHM has invested in have cost about $1 million so far.

“These developers have deep pockets and have been trying to run out the House’s funds,” Polich added.