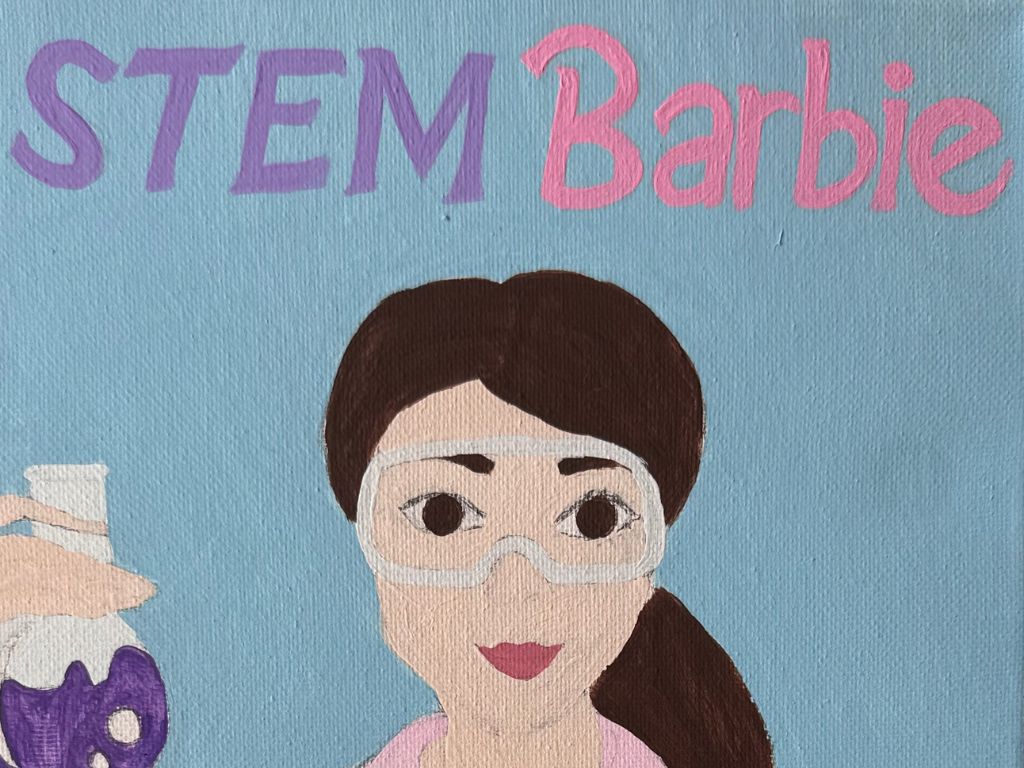

As the token, self-declared artist of the group (I had too much time on my hands the week before senior year), I made signs for all my soon-to-be roommates to hang above their doors. Keeping with the theme of “girl summer,” which had been three months of Barbenheimer and the Eras Tour, I gave each of us a Barbie-inspired canvas.

Without hesitation, my roommate Abby’s was “STEM Barbie.”

Abby Keiser, an associate scientist at Estée Lauder and prospective graduate student, is known for her unapologetic passion for science. In college, if she wasn’t in the apartment, she was likely tutoring athletes, in a five hour organic chemistry lab or working on a presentation about photothermal therapy. Which, as she translated to us non-STEM majors, means killing cancer cells with heat.

And if she wasn’t doing any of that, she was cooking, which is arguably a science in itself having seen the meals she cheffed up.

But as much as Abby likes chemistry, her true love is teaching it.

“The first semester I tutored made me completely fall in love with teaching, it was a no-brainer for me afterwards,” she gushed. “I would look forward to seeing them every week. It didn’t feel like a job anymore. I loved watching them build their confidence over the semester, and knowing I played a part in that was so rewarding.”

After graduating, Abby’s plan was to take a gap year, save up for graduate school and apply to education programs for the following year. She knew that an advanced degree would mean paying long term or taking out loans, but applying for a federal grant only occurred to her once she spoke with potential teaching programs.

“I realized that there was an option where I could maybe have my tuition paid for me, not only at state schools, but also at private schools,” Abby explained. “So it kind of widened my field of vision for where I could go.”

Having earned a degree in chemistry with honors, Abby’s used to understanding complex theories and solving intricate formulas. She’s even used to handling hydrofluoric acid at work everyday, a highly dangerous acid that can cause tissue damage. But when she received notice that the scholarship she applied to for her top program may cease to exist, even Abby was caught off guard.

Just weeks after Trump took office, the National Science Foundation (NSF) froze all existing grant payments that were deemed non-compliant with the administration. And shortly after that, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) announced a cap on overhead funds, blocking reviews from the Federal Register.

Then, she received the following email from the program director:

“This program may no longer exist due to an executive order from the President to freeze or eliminate NIH and NSF programs. As of today, we do not have any additional information from the government.”

Abby was at work when she read it, and her heart sank.

“I had been settling on the fact that I was going to be saving like $20,000 through a grant like this,” she told me. “It was really disappointing.”

She has since had to adjust her expectations for graduate school. Boston University was high up on her list because of its decent NSF program, which would’ve helped her pay for school, plus allow her to live somewhere beyond New York, something she’s never done.

Alas, Abby had to cut the school from her list. Paying in full would not be feasible with her young teaching salary.

I asked her if she would reconsider Boston if the NSF grant was resumed.

“Honestly, no,” she said. “I would still apply for the NSF, but only at Queens College, the state school, because I would feel okay knowing I could pay if it were to be canceled or taken away again.”

It’s this lingering sense of uncertainty that a lot of aspiring professionals are feeling, and not just for their own futures, but for the future of science as well. The NSF, for instance, prides itself on creating opportunities for historically underrepresented groups. So the freeze doesn’t just restrict access, it raises a systemic issue, she explains, since academic barriers are generally heightened for marginalized communities.

“And that’s really where STEM education needs to go, because we want these children to have opportunities to grow up, to get jobs in science fields, to become doctors and to pursue medicine,” said Abby. “But if they’re not given the opportunities, then they won’t be able to and that’s really unfortunate.”

I’ve had the privilege of watching Abby grow her knowledge of chemistry over the last four years, but more than that I’ve seen her be a thoughtful, kind human first. The type of person that should be teaching a group of kids.

When I was anxious for my anthropology final, it was Abby who stayed up quizzing me. When the roommates all had different graduation times, Abby live streamed it from our apartment and got everyone to watch.

She wants to see other people succeed, and then goes and celebrates them when they do. It’s the kind of teacher we all loved – and needed – growing up, and I know she will show her students that they can be STEM Barbies, too.