A Closer Look at Gangsta Rap

By Zac Howard

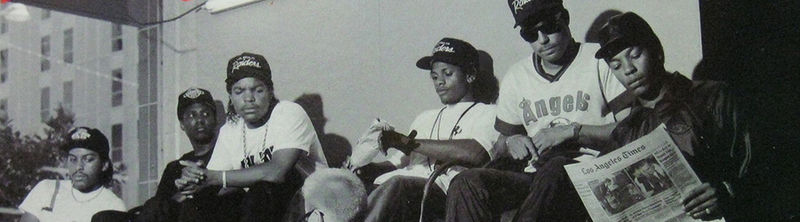

(Photo: Eric Poppleton / Wikipedia)

When President Obama invited Common to participate in the Evening of Poetry at the White House in 2011, it marked a substantial shift in the cultural positioning of hip hop that had taken place over the past quarter century. Nineteen years prior, vice president Dan Quayle denounced gangsta rap and called for Time Warner to pull Ice T’s “Cop Killer” from the shelves. Quayle and President Bush were merely the highest ranking of countless government officials and voices in the community to call for censorship.

Many criticized President Obama’s decision, but it was a far cry from the societal outrage that marked the 1990’s gangsta rap rhetoric. Quayle’s dismissal of the genre’s polarizing content may seem a distant memory now, but the concept of explicit lyrics in rap music serving as a form of protest art remains active and the imprint of gangsta rap during its peak is evident across the national landscape.

“Gangsta rap is still very much alive today, it just has different names,” says Ben Westhoff, author of Original Gangstas, which is set to be released in September. “The drill scene in Chicago, trap scene, ratchet scene. There’s still a ton of very popular rappers that have these gangster tropes,” Westhoff says.

Westhoff points out that the recent success of Straight Outta Compton indicates a more welcoming American public than the one that existed in 1988, when NWA’s controversial album first dropped. “For the most part, gangsta rap has been accepted as a form of protest art,” he says. “It’s all become very mainstream now.”

While the acceptance of this art may be a recent occurrence, the concept is certainly not new. In his 1995 essay “Gangsta Rap and American Culture,” Dr. Michael Eric Dyson defines these artists as “privileged persons speaking for less visible or vocal peers.” The essay criticizes many elements of gangsta rap, including misogynistic and homophobic lyrics, but also suggests that using the authors as scapegoats for larger problems is not the answer.

“Artists are saying, ‘If you don’t like our lyrics, change the conditions so that’s not the reality.’”

Dyson goes on to say, “At their best, rappers shape the tortuous twists of urban fate into lyrical elegies. They represent lives swallowed by too little love or opportunity. They represent themselves and their peers with aggrandizing anthems that boast of their ingenuity and luck in surviving.”

“The argument is always that the artists are saying, ‘We’re describing our reality.’ It’s a description of what is going on in the community,” says Andrew Mannheimer, a PhD student and co-teacher of “The Sociology of Hip Hop” at Florida State University. “Members of the dominant culture often act like this problem does not exist or it’s being caused by hip hop, whereas the artists are saying, ‘If you don’t like our lyrics, change the conditions so that’s not the reality.’”

However, these vivid descriptions were accompanied by other lyrics that brought about criticism—some of which came from those with similar backgrounds as the rappers. Respected names in the industry such as Chuck D of Public Enemy and Afrika Bambaataa have spoken out against ganster tropes in rap. The murders of Tupac and Notorious B.I.G. in 1996 and 1997, arguably the biggest names in the genre at the time, sent shockwaves throughout the hip hop community. “Things calmed down and people tried to make peace after that,” Westhoff says.

In addition to the climactic East Coast West Coast ceasefire, time itself has been a contributing factor in the acceptance of gangsta rap. “Historically, NWA is being looked at as a group that had a message that had a significant impact on hip hop and American society,” says Mannheimer. “I think it’s viewed more positively now than when it first came out, but that’s not unique to hip hop. Jazz music used to be seen at as deviant. Rock and roll used to be seen as deviant.”

Perhaps a few more decades will bring about even greater change. “I imagine I’ll be talking to my grandkids, and there will be this new genre of music they’re listening to and I’ll say, ‘You all need to get back to some good old hip hop,’” Mannheimer says. “Just like people today are saying, ‘What happened to jazz, what happened to soul, what happened to rock and roll.’”

The debate about artists writing authentic lyrics in an industry fueled by entertainment extends beyond hip hop into the music world as a whole, but discussions are particularly interesting when the fraudulence pertains to criminal activity. In 2008, The Smoking Gun revealed documents proving Rick Ross worked as a corrections officer prior to his rise to stardom. Ross’s staunch denial of the fact, after photos of him in uniform had previously surfaced, reminded fans that listening to personal testimony in hit songs may not be tantamount to reading an artist’s diary.

Dyson discusses this reality in his essay, saying, “Many gangsta rappers helped to create the genre’s artistic rules. Further, they have figured out how to financially exploit sincere and sensational interest in ‘ghetto life.’” An ancillary question can be asked about the listeners of gangsta rap. Why do such violent, graphic lyrics appeal to so many demographics?

“I think most great artists are great storytellers,” Mannheimer says. “Some people relate directly to the picture they’re painting. Other people may be completely detached by that lifestyle, but they’re intrigued by it. And then other people consume it just as entertainment. They may not even believe it, they might not think critically about it.”

As a result, the consumption of gangsta rap is manifest is a variety of ways—making it’s impact and attraction wide-reaching. “Why are all these different demographics gravitating towards this story? One of them is connecting, one of them learning, and another one is just being entertained by it,” Mannheimer says.

The results of this consumption are difficult to measure, but Dyson anticipated such possibilities over twenty years ago amidst controversy and turmoil. “We should not continue to blame gangsta rap for ills that existed long before hip hop uttered its first syllable,” he wrote. “Indeed, gangsta rap’s in-your-face style may do more to force our nation to confront crucial social problems than countless sermons or political speeches.”