On Fly Fishing and Style with David Coggins

By Laurenz Busch

On the cusp of the one-year anniversary of The Optimist, West Village resident, men’s style aficionado, and devoted angler David Coggins is well into the depths of his second book about fly fishing. Planned for May 2023, it’s called The Believer. Having made his mark on the book world with the New York Times bestseller Men and Style (2016) and Men and Manners (2018), Coggins has turned his focus towards the angling journeys that have taken him to some of the most remote and beautiful places in the world.

During the pandemic, Coggins also started a newsletter called The Contender. Having built a strong and loyal base, he’s taken them along with him on philosophical forays into travel, fishing, style, and the quest for meaning. Along the way, he’s provided insight into a life lived well, both aesthetically and practically.

In our conversation, we explored the lines between public and private – something that has blurred in recent years – as well as mentor and student. Men’s style, of course, also came up in our discussion. His appreciation for goods that have been well-loved, that portray connection and personality, remains strong. In the process, he advocates straying from the easily attainable world of constant and perhaps unnecessary innovation.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

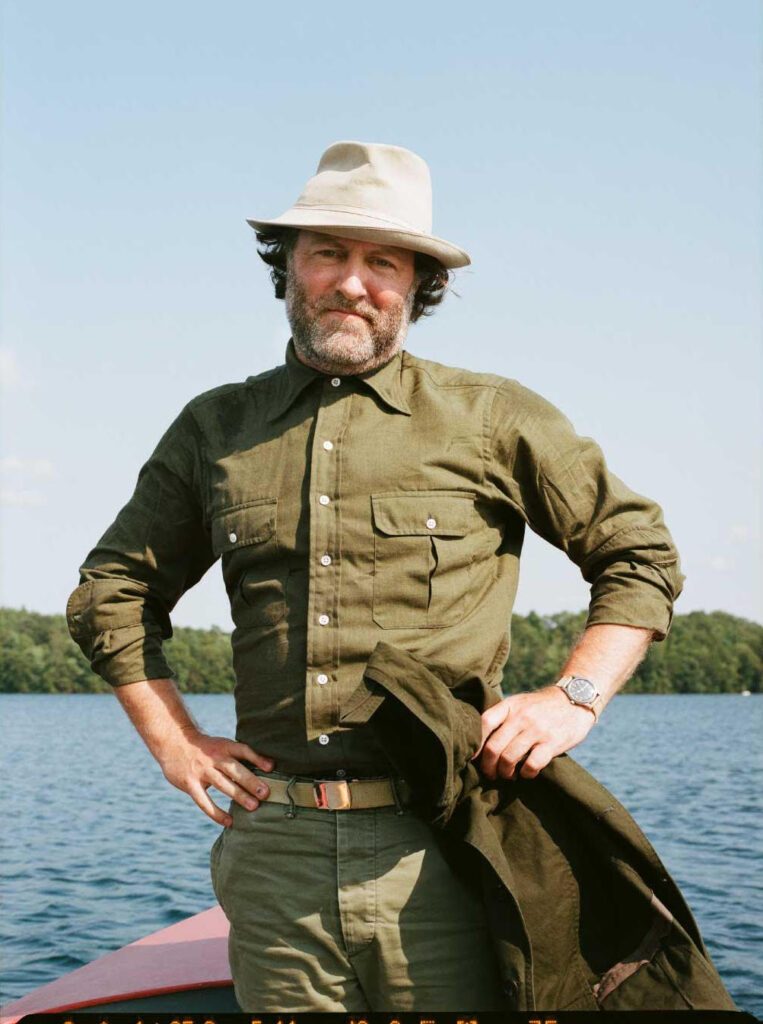

David Coggins. Photo by: Spencer Wells

In every chapter of The Optimist, except for the afterword, there’s someone else with you – a mentor, or a guide or a friend. Why are these people and trips integral to The Optimist?

Fishing is so often about solitude, self-containment, and self-assessment – because you’re trying to get better at something, you’re struggling to accomplish something, and most often you’re failing. And yet fishing can be extraordinarily social and even intimate with a friend or guide. As it happens, the first people who taught me were friends of my grandfather, who had made a very strong impression on me. They were mentors to me, though, I don’t know if they would have used that phrase – they both passed on.

I’m working on my next book called The Believer. It involves several fishing pilgrimages. In [the book], each person was very carefully chosen [for their philosophies]. I know what they think, and not just about fishing but about life in general. So, in that case, that was a little more self-conscious. It was more accidental with The Optimist because I couldn’t have chosen the people that taught me.

In regards to the mentor or the guide – surely someone with your experience doesn’t need them anymore. Why was it important to position yourself as a student but also as a guide to the reader?

The guide lives a life that I can’t – he’s on the water 150 days a year or more, he’s made decisions that I’m both envious and frightened of. When you’re with someone in Argentina, maybe you think, oh, I want to live in Patagonia – you want to imagine that, but you can’t really do it, you’ve got other responsibilities. It’s easier to pretend you want to do it than to actually do it.

What I was trying to do with the book was – it’s complicated writing a fishing book, because you have many different audiences – and I’ve tried to be fairly clear upfront that this isn’t a book that’s going to teach tactics to hardcore anglers – there are many people who can do that much better. And what I’m trying to do is give some sense of what’s at stake to a casual angling reader, and some sense of what you’re trying to learn for a person who’s new to the sport or doesn’t fish at all.

Your car is an angler’s dream – an older Volvo station wagon, neatly organized to suit the obsession, and aesthetically oriented. There’s an inherent Emersonian ideal of self-reliance when you’re out in your car and you’re able to stray further from the comforts of society – does that ideal play into your everyday life?

I don’t know if I would actually say I’m self-reliant. I want to approach that, but I still want some sort of reassurance. I love the idea of driving west, of having a car, and if you’re an angler you have these thoughts about how much you need, what you need. If you travel to a place, you’re bringing all your gear with you, so you try to imagine everything you might need. And that gets people really revved up. Everyone has a different definition of what they think they need.

I spend a large amount of time in Wisconsin each summer – that’s where the book begins. My family’s cabin represents to me the antithesis to my life in New York. I view angling as a counterbalance to my urban life, city life, and cultural life. I think it’s important for me to care about the opera, the arts, and literature, and then to go into the natural world where those things don’t exist. Only the memory of them exists. I think one thing that surprised me the first time I went to the flats in the Bahamas. It was the most horizontal and the most isolated place I’ve ever been – in a way that’s different than the desert, which is a little more stark. I was very moved by that. I’m still affected by that feeling of isolation and like seeking that out. I wasn’t prepared for how I would feel in those settings.

There was once a sort of divinity about being a writer in New York, so what’s it like to be a writer in the West Village in an almost-post-pandemic world?

It’s strange – it’s interesting and confusing and exciting and overwhelming all at the same time. If I have a chance to talk to someone who wrote for print magazines in New York in the ‘70s and ‘80s, it’s very exciting. It seems like half the magazines I’ve written for are out of business. The relationship to print and to a singular publication rarely exists for any writer and I think I was lucky when I began writing – I was an arts writer and I wrote for very serious editors. That doesn’t exist for many people now. Having said all that, there are many other possible ways to write and to get your words and stories out into the world.

I started a website in 2019 called The Contender. One reason I did that is because I was writing for brands that hired me to write essays and other publications. My writing was all over the internet and people couldn’t really find it in one easy-to-consume place so I started a website – that was quite satisfying. It was a blog basically, I called it a site just out of pretentiousness. I was trying to write things that were more polished, but oddly, when the pandemic began, I started to write more personally and I could tell that that was connecting with people who didn’t have someone writing in real time to connect their feelings of loneliness or isolation with. That evolved into a newsletter, also called The Contender, which has been a great thing for me. Newsletters can be very, very good and can really connect you to an audience, if you have a devoted following.

You’re giving me a lot to think about.

When I was young, I learned from Glenn O’Brien who wrote a monthly column in Artforum – he later became the first editor of Interview Magazine. He wrote the introduction to my book Men and Style, and that was one of the biggest honors of my life. Glenn taught me so many things, and I vowed if I ever got to be in a better position, I would help young people because I appreciated the help I received so much. It’s an important thing that’s easy to forget, to lose the thread about how we all got here. Everyone’s so busy, self-promoting on social media – which I’m guilty of that too – but we’ve lost a little bit of the connected thread that is important.

You’re obviously no stranger to tailored clothes. The pandemic brought on a whole new understanding of leisurewear, what did the pandemic bring on for you? How have you been able to continue your appreciation for fine clothing during the pandemic?

What the pandemic taught me and what I took away from it is the importance of the distinction between public and private. This idea of dressing up and presenting yourself in public and how you behave in public. I think that culture has really lost the distinction between public and private, for many reasons. There’s this absurd idea about comfort: I need to be comfortable all the time. That can mean dressing. It can also mean speaking loudly on your phone, having a full volume conversation on FaceTime, or saying something on Twitter in public that should be often left in private – people feel entitled to express these opinions without any real consideration about how it impacts other people.

As far as dressing goes, what people realized when they were home, is that they missed being in public. Most people at first were like, oh, it’s so great – even though I didn’t think it was great – I can sit around and not dress up in my office clothes or I can wear whatever I want. Very quickly that got tiring for them because they had no choice, they had to be home. And then all of a sudden, they wanted to go out and not just go out, they wanted an experience that really felt like they were out – like the opera. It’s no surprise to me that young people wanted to go to Bemelmans Bar. That’s a really traditional bar – you really feel like you’re in New York when you’re there, it’s very celebratory, very formal, very old world.

David Coggins. Photo by: Spencer Wells

What are some of your favorite tailors in New York?

Well, I mean, my friend Jake Mueser [J. Mueser Bespoke], he’s located on Christopher Street and his clothes are mostly made in Naples, Italy – which is probably the best place to have clothes made, and the guys who work with him are great. My friends at Drake’s run probably the best men’s store. They’re in a temporary location on Canal Street, their website is amazing, their editorial is great. Those are my two main places.

What do you think is the first item that someone should buy tailored?

An unstructured sport coat. That is the easiest and most versatile thing to wear. For a lot of men, they get revved up when they’re finally going to a tailor and they want to have something extremely unique, extremely one of a kind. Then it’s a little hard to wear, so they don’t wear it as much as they should. I think they should get something slightly less interesting. When you get to a very extreme level of obsessiveness, then you can start talking about you know, herringbone, or whatever else it is.

I write about this a lot – I turn The Contender newsletter once a month or so into a Q&A in the comment section. I get hundreds of questions and it’s really fun to see what people ask. They’re paid subscribers, so they’re already kind of into this world and they’re asking the most detailed questions.

When you’re amongst anglers in Montana or Wisconsin, how do you bring your acute awareness of detail and appreciation for men’s style into the conversation?

Tailored clothing is an expression of a historical point of view. If you’re on Savile Row, you understand the history of why these clothes exist. Angling clothes or field clothes are purpose-driven. That’s why you have wax cotton or tin cloth or technical fabrics. If you’re fishing in England, there’s a lot of very traditional people who actually wear tweed clothes to fish. That’s pretty rare for me. Some people even wear ties because the trout is the gentleman of fish, so you dress appropriately. I don’t do that, and I would never do that in Montana. I don’t mind being on the more formal side of things, what I like are pieces that are true to your personality but also serve a purpose and represent what you like about the history of the sport. All those things converging is very interesting to me. When I see someone who has what I can tell is a lucky hat, or he’s wearing something that seems like he inherited from his father or grandfather – I love that stuff – something that communicates a connection to that object, and isn’t just getting the newest thing each year – especially some nonsense made-up trend designed to sell.

Almost like a spiritual patina.

Exactly! If you go to the L.L. Bean Archive or a Filson store and you see some super old tin cloth jacket, it’s so great to see that because someone has worn it for its intended purpose. There’s a connection. You often see it with bags, a man who has an old leather bag, especially if it was fancy at some point – he’s stuck with it.